Spinning Greenwash: How the fashion industry’s shift to recycled polyester is worsening microplastic pollution

A new study commissioned by the Changing Markets Foundation and carried out by the Microplastic Research Group at Çukurova University finds that recycled polyester, the fashion industry’s flagship ‘sustainable’ solution, sheds more microfibres than virgin polyester. Testing of 51 garments from Adidas, H&M, Nike, Shein and Zara showed that recycled polyester releases both the highest number of fibres and the finest particles,worsening the microplastic pollution problem.

Fashion brands regularly market recycled polyester as a ‘preferred fibre’. Changing Markets’ 2024 Fashion’s Plastic Paralysis report found that 82% of brands that responded to the questionnaire plan to increase its use, with some pledging full transition by 2030. Yet according to industry figures 98% of recycled polyester comes from plastic bottles, not textile waste. Brands market this as circularity: Nike claims that its use of recycled polyester made from plastic bottles helps in ‘reducing waste’ by diverting around one billion bottles each year from landfills and waterways; Adidas states that ‘the use of recycled plastic in products is part of the company’s efforts to avoid plastic waste and stop the pollution of the world’s oceans’; and Shein markets its recycled polyester garments through a glossy video depicting a bottle’s journey into clothing.

In reality, bottle-to-textile removes bottles from closed-loop recycling, downcycling them into garments that shed microplastics and cannot be effectively recycled again, ultimately ending up in landfills or incinerators.

Major brands already rely heavily on this false solution: Adidas claims that 99% of its polyester is recycled, and H&M reports that in 2024, 94% of the polyester it sourced was recycled. Even Patagonia — often held up as a sustainability leader — discloses that 93.6% of its polyester is recycled (mostly from plastic bottles), which represents more than half (52%) of its entire materials.

Recycled polyester has become a convenient cover for the industry, allowing brands to claim progress on reducing virgin plastic reliance while increasing overall synthetic fibre production. Textile Exchange data shows this clearly: although recycled polyester volumes rose last year, its overall market share fell from 12.5% to 12%, because virgin polyester grew even faster.

This trend unfolds amid an escalating plastic crisis. Annual plastic production has surged from 2 megatonnes (Mt) in 1950 to 475 Mt in 2022, and is projected to hit 1,200 Mt by 2060. Roughly 8,000 Mt of plastic waste now contaminates the planet’s land, air and oceans. A newly released report, by Pew, Breaking the Plastic Wave 2.0 (December, 2025), finds that plastic pollution is set to more than double within 15 years, driven largely by packaging and textile production. The report estimates that by 2040, annual plastic waste leaking into the environment will rise from 130 Mt to 280 Mt, far outpacing improvements in waste management. It also finds that while packaging will remain the biggest plastic user until 2040, textiles will experience the steepest growth, fuelled by the rapid expansion of low-cost synthetic clothing. These plastics break down into microplastics, now recognised as one of the most pervasive forms of pollution. They contaminate soil, water, air and enter the food chain, with growing evidence of harm to ecosystems and human health. Synthetic textiles are estimated to generate up to 35% of primary microplastics entering the ocean. Microplastics have been detected in the human stomach, circulatory system, placenta and numerous other organs and are linked to a higher risk of stroke, heart attack, cardiovascular disease, inflammation, hormonal disruption and premature death.

The fashion industry sits at the heart of this problem, driven above all by polyester: synthetic fibres made from fossil fuels account for around 69% of all textile production, with polyester making up the majority, accounting for 59% of global textile production. Its low cost — around half that of cotton — has fuelled a surge in cheap, disposable clothing; since the early 2000s, polyester’s rise has doubled global fibre output, cementing its place as a key driver of the fashion industry’s growth. This dependence spans the entire sector: ultra-fast-fashion giant Shein uses synthetics for about 89% of its production, with 82% coming from polyester, while Patagonia relies on synthetics for roughly 80% of its materials, with 56% from polyester.

Fashion’s Plastic Paralysis found that although most companies acknowledge microplastics from synthetic fibres as an environmental issue, few have taken meaningful or measurable action to address it. Concerns about bottle-derived recycled polyester are shared by Europe’s beverage industry, which has urged policymakers since 2021 to stop the downcycling of plastic bottles into textiles. They warn that fashion’s growing demand disrupts closed-loop bottle-to-bottle recycling and puts both sectors in direct competition. This concern is backed by McKinsey projections showing that, by 2030, recycled polyester demand will be three times higher than available supply in the US.

At the same time, the fashion industry has deflected attention from synthetics by promoting claims that natural fibres such as cotton or viscose shed similar or even greater amounts of fibre. It has highlighted studies reporting that natural fibres were more common than polyester in coastal seawater along the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts, and that most microfibres found in fish come from cotton or wool. These findings are used to argue that all fibres deserve equal attention and that synthetics should not be singled out. In 2023, the industry published a widely cited study claiming that mechanically recycled polyester sheds no more than virgin polyester.

Our study helps to fill the evidence gap by comparing microfibre shedding across fibres from well-known brands, providing independent data to guide policymakers, consumers, and industry in reducing textiles’ environmental impact.

This study

We analysed 51 garments from Adidas, H&M, Nike, Shein and Zara, testing virgin and recycled synthetics alongside natural fibres. For most brands, this included three cotton, three virgin polyester and three recycled polyester items. We selected garments of broadly comparable size and type (T-shirts, tops, dresses and shorts). However, limited information on production methods and textile construction meant this was not always possible.

Although this study reveals the microfibre release from garments made with specific fabrics and yarn types on selected production lines, it represents only a consumer-level snapshot of shedding behaviour that signals broader industry trends. A more comprehensive assessment would be required to capture the full scale of impacts across the large production volumes of the brands examined. The study also has limitations, including differences in garment types and construction across brands. Although the sample size may appear small, in tests of this kind, the numbers can be considered statistically significant because garments are produced in long, uniform fabric runs; one item is therefore representative of an entire production batch rather than a single product.

We tested the items using two recognised laundering systems:

- The GyroWash (measuring fibre count and fibre size). This method is only used for garments with a uniform fabric structure suitable for cutting consistent 4 × 10 cm samples. 40 items were able to be tested this way.

- The Wascator (measuring total fibre mass loss) – all 51 items were tested through this system.

Both washing systems simulate household washing but answer different questions, allowing us to compare shedding across fibre types in terms of fibre number, size and fibre mass.

The main purpose of the study was to compare fibre shedding between fibre types. In addition, we assessed whether the fibre shedding behaviour of any brand was significantly different, using the ANOVA statistical test to compare the average results from the five brands. Full methodology is available in the report download bar.

Main findings

- Recycled polyester sheds the most microfibres

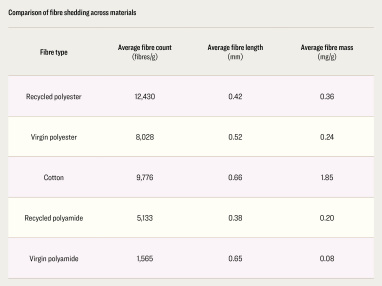

A sample of 23 virgin and recycled polyester items revealed that recycled polyester released ≈12,000 fibres per gram on average — 55% (54.8%) more than virgin polyester (8,028 fibres/g). We believe that this is an underestimate, as when we removed Shein’s items because of our suspicion that their ‘recycled polyester’ garments may in fact be made from virgin polyester (see point 5), the discrepancy in fibre shedding between recycled and virgin polyester increased to 72%.

Recycled polyester fibres were also consistently smaller than those of virgin polyester (with an average length of 0.42 vs. 0.52 mm), increasing toxicity, environmental dispersion and chemical load. Because each fibre is a separate particle, it can be inhaled, ingested, transported through ecosystems, or carry harmful chemicals. Smaller fibres carry greater environmental and health risks — they travel further, penetrate deeper into lungs and tissues, and are more readily ingested by aquatic and soil organisms. A larger sample of 29 items testing for fibre mass loss (12 virgin polyester, 17 recycled) also indicated that recycled polyester lost 50% more mass than its virgin counterpart (0.36 vs 0.24 mg/g).

- Recycling worsens shedding for synthetics

Recycled versions of polyester and polyamide both shed more than their virgin counterparts. While recycled polyester shed approximately 55% more fibres than virgin polyester (12,430 fibres/g vs. 8,028 fibres/g), recycled polyamide shed over three times as much as virgin polyamide (228%; 5,133 fibres/g vs. 1,565 fibres/g). We tested for polyamide as for one brand, Zara, we were unable to get recycled polyester. - Cotton sheds heavier, longer fibres

Our tests focused on virgin cotton and found that it released 1.85 mg/g of heavier, longer fibres (0.40–0.94 mm),[6]which are less likely to reach the lower respiratory tract, potentially posing a lower health risk compared to smaller, inhalable fibres.

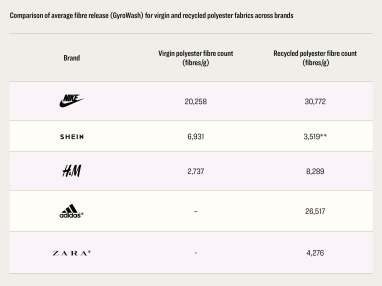

- Shedding is systemic, but some polyester results stand out

The study found minimal differences between brands, indicating that microfibre shedding is a systemic industry-wide issue driven mainly by material and production choices. However, across polyester fabrics, Nike showed the highest fibre release in both virgin and recycled polyester. Nike’s virgin-polyester items released on average around 20,258 fibres per gram of garment sample — nearly three times more than Shein (6,931 fibres/g) and over seven times more than H&M (2,737 fibres/g).

Nike’s recycled-polyester was also the highest-shedding across all brands tested with an average of 30,772 fibres/g): releasing around 16% more fibres than Adidas, nearly four times more than H&M, and seven times more than Zara (see section 2.2.4 of the report).

*No virgin polyester items from Zara were found for purchase through the brand’s online store and Adidas virgin polyester samples did not come from uniform fabric and therefore were not suitable for testing through GyroWash.

**We suspect Shein’s ‘recycled polyester’ garments may in fact be made from virgin polyester (see point 5).

- ‘Recycled polyester’ claims may be misleading

When selecting garments, we found repeated discrepancies between brands’ online claims and the fibre content listed on physical labels, raising doubts about the accuracy of recycled polyester claims. Shein’s items advertised as ‘recycled polyester’ in June 2025 when we purchased the garments, were months later relisted simply as polyester. This is likely to explain why Shein’s samples, initially sold as ‘recycled’ showed shedding levels (3,519 fibres/g) similar to its virgin polyester items. We found similar inconsistencies appeared in some of the samples purchased from H&M and Nike, where garments marketed online as containing recycled polyester did not state this on their care labels. These findings highlight the need for stronger oversight, clear labelling rules and independent verification to prevent fraud.

Broader implications and the way forward

This study’s findings challenge the industry narrative that recycled polyester is a solution to plastic pollution. Environmentally and biologically, recycled synthetics worsen microplastic pollution by increasing the number of fibres released, their toxicity, their ability to disperse, and the total mass entering the environment.

While smarter design and manufacturing choices, such as using continuous filaments, higher-twist low-hairiness yarns, tighter weaves, laser-cut edges, industrial pre-washing, fibre-capture systems and non-toxic finishes, can help reduce microfibre release, these are only partial fixes. The fundamental solution is to reduce the use of both virgin and recycled synthetic fibres. This is because no amount of fibre optimisation and filtration technologies can fully eliminate the pollution they create.

Achieving fundamental — and even intermediate — solutions will require strong regulatory measures. The EU should introduce eco-design criteria with mandatory testing and labelling of all fabrics for shedding performance, microplastic emission limits in finished products, and clear consumer warnings on synthetic textiles. Policies should also account for the ecotoxicity impacts of microplastic release in life-cycle assessments, mandate industrial pre-washing and promote innovation in low-shedding materials.

The delayed EU initiative on unintentional microplastic release must be revived, and the revised Waste Framework Directive should include fees linked to microplastic emissions and product volumes to curb overproduction and help incentivise a real shift toward producing fewer, higher-quality and lower impact garments.

Beyond the EU, a global plastics treaty that sets limits on virgin plastic production and prioritises source reduction would help address the root causes of microplastic pollution, ensuring that fashion’s growing reliance on synthetics does not continue unchecked.

Meanwhile, consumers can help reduce microplastic pollution by buying fewer, better-quality garments, washing less and on gentler cycles, and avoiding ultra-fast-fashion items made largely from synthetics. They should also be wary of potentially misleading ‘recycled polyester’ claims, and make efforts to support brands which are genuinely reducing their reliance on plastic-based fashion.

Detailed policy and brand recommendations are presented at the end of the report.

You might also like...

Dressed to Kill: Fashion brands’ hidden links to Russian oil in a time of war

This report exposes the hidden supply chain links between major global fashion brands and retailers and Russian oil used to make synthetic clothing.

Crude Couture: Fashion Brands’ Continued Links to Russian Oil

This report offers a one-year follow-up from the "Dressed to Kill" report, evaluating whether fashion brands have ended their connections with contentious suppliers using Russian oil and coal.

Synthetics Anonymous 2.0: Fashion’s persistent plastic problem

Synthetics Anonymous 2.0 uncovers the lack of progress that has been made by the fashion industry to kick its synthetics addiction.